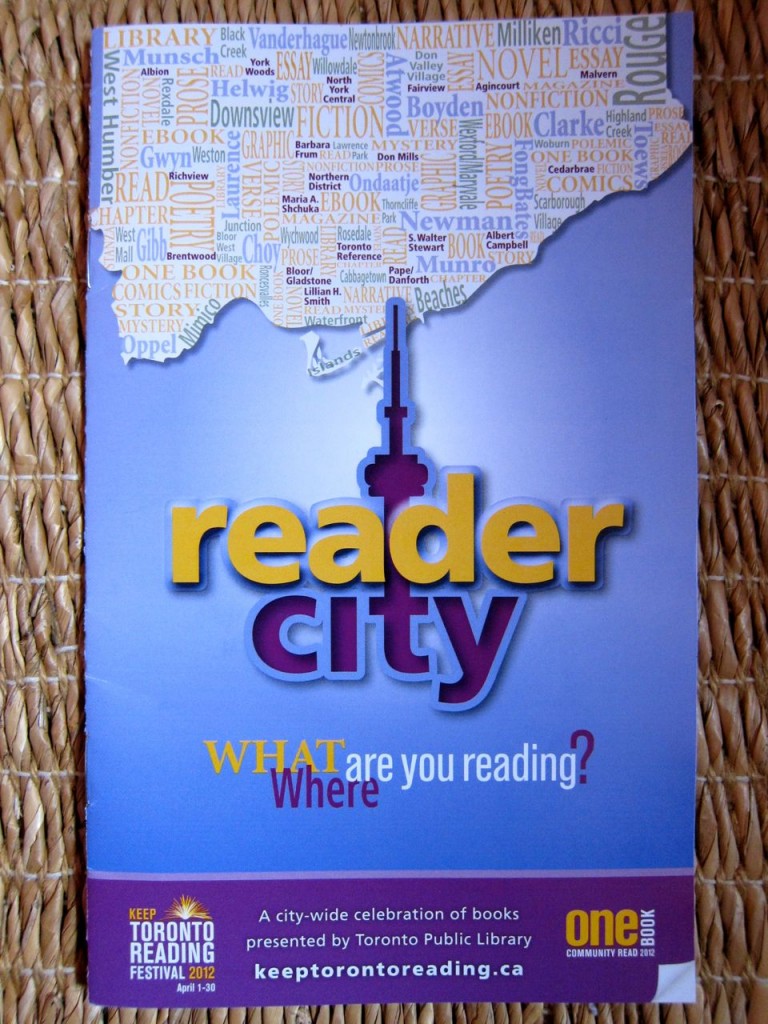

Last week I listened to the personal testimony of Holocaust survivor Denise Hans at North York Central Library. A very large group of teenagers and adults filled the library auditorium, creating an audience five times the size of the Holocaust Education Week programs I’ve attended at Deer Park, Mount Pleasant, and High Park.

The speaker explained that she started giving these talks four years ago. “I do it to pay homage to my mother. Without her, I wouldn’t be here with you today.”

I’m grateful to Ms. Hans for modeling the courage it takes to share an excruciating personal account with strangers: “In 1942, after (Denise’s) father, aunt, and uncle were taken from her home and murdered, her mother sought places to hide her six children and two nieces” (31st Holocaust Education Week program booklet, p. 26). This stark summary cannot fully capture the experience of listening to Denise’s testimony in person. Her animated voice, the range of expressions on her kind face, and the vivid description of her childhood memories made her narrative of survival come alive in my mind.

The fourth of six children, Ms. Hans was born in Paris in 1938. To this day, she remembers the colourful visors her mother used to sew on the brims of hats. She remembers her father’s delivery tricycle with its large box in the front (into which he’d put a couple of his children on Sundays and take them on an exciting ride around Paris). She remembers her regret over teasing her six year-old brother for having to wear the yellow star of David when she was too young to wear one. And she still remembers the first cries of her baby sister, Monique (who was born at home because Jews were barred from the hospital), even though Denise was only three and a half at the time.

The speaker also recalled the grit and bravery her mother displayed after her father was taken to a holding camp. She managed to get a pass for her husband to visit home by setting her crying baby on a Gestapo officer’s desk, saying, “If you can’t let my husband out to support his family, then you take care of the baby.” The officer’s face became redder and redder as the baby’s howls set off a chain reaction of crying among her older siblings. “You can’t imagine what a huge noise and hullabaloo we made!” said Denise. The officer quickly wrote the pass and sent them on their way.

When Denise’s father returned home, the children had to pretend he was a family friend. It was hard to remember not to call him affectionate names and address him as Monsieur instead. By this time, Denise’s aunt, uncle, and two cousins were living in the house, too. They planned to use the secret entrance to the attic and hide there in case they heard a knock at the door that wasn’t the family’s special knock. However, when the dreaded home invasion came in 1942, there was no time to hide four adults and eight children. A Nazi took all the adults except Denise’s mother away to the police station. They were never seen again.

Denise’s voice shook when she said, “I was only four years old when my father was taken. Do you know that I can still remember every line on the Nazi’s face, but I can’t picture my father’s face?” And the sadness she felt for her mother, who lost multiple beloved family members in a single day, suffused the speaker’s voice as well.

After the murder of Denise’s father, aunt, and uncle, her mother was the sole comforter and provider for eight children. She was only in her early 30’s. At night, the four youngest children were very frightened, so they crawled into bed with their surviving parent, each one claiming a maternal limb to hug all night long. Denise said, “The right leg was mine. I remember pressing my cheek against it for warmth. Everybody was so busy during the day that there was no time for hugs and kisses for the children.”

Soon, Denise’s mother realized that she needed to find a hiding place for all the youngsters in her care, and the first of three locations she secured was at a farm house in the country. The farmer’s wife wasn’t kind to the eight children that she hid, and she cut off Monique’s beautiful blond curls because she falsely assumed she had lice. Worst of all, she didn’t give the children enough food. Denise’s mother realized that her children were starving after she arranged to have her youngest child visit her briefly in Paris. She gave the little girl some hot chocolate and cookies, and when a few crumbs fell to the floor, the child got down on her hands and knees and licked up the crumbs.

A new hiding place at a second farm was found, this time with a more congenial family. However, the children had to be split up, and another sorrow for Denise was the daily task of scratching the legs of the new family’s teenage daughter, who suffered from a skin disease. “It was a disgusting job, I tell you.”

A Sisters of Zion convent was the last war-time shelter Denise’s mother found for her children. By this time, the Nazis were not able to meet their quotas of Jews to fill the death camps because they had already rounded up so many. (One shocking historical fact that I learned from Ms. Hans was that the Vichy government made a deal with the Nazis that they would allow them to take the Jews of the unoccupied Free Zone of France in exchange for not bombing the monuments of Paris).

For safety, Denise’s mother requested that the children be baptized. The Sisters took all six girls, and the boys were sent to an equivalent Catholic institution. “The Sisters were strict, but I enjoyed my time in the convent. I loved the pageantry of the masses, and I enjoyed Christmas and Easter.”

In 1948, “les trois petites” (the three youngest girls, including Denise) were finally re-united with their mother. The older five children had returned earlier because it would have been difficult to support all eight right at the end of the war. “One day, the Sisters summoned us and said that we were going home because we had a new father. A new father? We were really surprised, but in those days children didn’t ask questions.”

Determined to remove Christian symbols from his home and his step-children’s possession, Denise’s new parent tore up the “beautiful cards of Jesus that the Sisters gave me,” in an understandable reaction that nevertheless was a big “culture shock” for the ten-year old Denise, who had spent a good portion of her childhood in a convent. “We couldn’t complain, though. We were alive and his children weren’t.” She shared her feelings of regret that she not only lost her father but her mother as well during the war: “I was separated from my mother for six years. I’m still sad about this loss today.” As Denise Hans’ testimony drew to a close, I could hear crying in the audience for the child who had suffered so much grief, deprivation, and terror.